The Grapple Annual No. 2: coming soon

It seems The Grapple Annual No. 1 has had a pretty sweet time out in the world. People have said good things about it, reviews have been positive and copies are almost sold out (almost – not too late to get a copy). Plus, hey, it won the Small Press Network’s Most Underrated Book Award in 2015. So far, so good, so we’d better not stop there. And we have not at all; we’ve been heartily working on another.

Coming soon in 2016 will be The Grapple Annual No. 2. After several hefty rounds of submission selections and editorial collaborations, we have locked in 42(!) works for this Annual. Again, each work relates in a unique way to its own special date on the calendar. And, again, this will be a book full of diverse but uniformly excellent prose, poetry, art and comics for you to both grapple with and enjoy. This time, they’ve come from 42 writers and artists from many places on the planet: Canberra, the ACT region and many other Australian locations, but also the UK, the USA, Canada and Egypt. We’re immensely proud to be publishing each and every one of them. This Annual has been long-awaited, but it’s gonna be totally worth it.

So while we’re making the final editorial touches and designing the book that will somehow contain it all, we’d like today for you to share in our anticipation. There will be more news soon, including further call outs, release dates and launch details. But for now …

*ahem/deep breath/drum roll*

The Grapple Annual No. 2

FEATURING:

– Braille by Louis Klee (4 January)

– Hydra by Emma Marie Jones (11 January)

– 28 January by Soraya Morayef (28 January)

– Loss by Alice Bishop (7 February)

– Racey Friends – looking by Paden Hunter (12 February)

– Nightdriving by Alexander Bennetts (28 February)

– Fairy Goddaughter by Sarah Pritchard (6 March)

– Beware the Ides of March! by Sam Brien (15 March)

– The Connected World by David C Mahler (21 March)

– Visiting Richard Yates by Elizabeth Caplice (25 March)

– March Camping, 1990s by Christopher Evans (26 March)

– Dreamcast Monolith with Undergrowth by Alice Carroll (31 March)

– Meander, Triste and Awe by Brett Canét-Gibson (14th April)

– Divine Vinyl by Owen Heitmann (16 April)

– From JG Ballard, July 1966 (behind Foot Locker, August 2013) by Andrew Galan (19 April)

– Today I Feel Like Remembering by Anna Jacobson (22 April)

– Thoughts on art and the ways it reaches you by Sandra Hajda (29 April)

– May, The Opening by Ben Walter (1 May)

– Mahala by Fikret Pajalic (5 May)

– The Drunk and the Flower Man by Nathan Fioritti (11 May)

– What If? by Miranda Cashin (15 May)

– The River Fisher’s Daughter by Kirk Marshall (25 May)

– Baby Emma by Emma Makepeace (1 June)

– All these places have their moments by Madeline Karurtz (12 June)

– After Life by Lauren Briggs (23 June)

– The Golden Age of Science Fiction by David Stevens (7 July)

– The 8th July in History by Safdar Ahmed (8 July)

– Positive Space by Lynley Eavis (21 July)

– The End of Days by Jack Martinez (1 August)

– When They Were Young by Shuang West (13 August)

– Audley by Humyara Mahbub (14 August)

– The Gurindji People by Mandy Ord (16 August)

– Go Troppo by Isabelle Li (17 September)

– Campo de’ Fiori by Ashley Capes (22 September)

– Rule Ten by Gregory Wolos (28 September)

– Four Confessions That I’ve Been Meaning to Confess Since That Evening When We Made Guacamole and I Compared All Three Avocados to my Womb, Which Might’ve Made You Uncomfortable but I Couldn’t Tell for Sure by Kayla Pongrac (29 September)

– Pilot Episode, October 2nd by Lauren Paredes (2 October)

– I Desire; I Have Our Home by Emma Rose Smith (2 November)

– Great Emu War by Eleri Mai Harris (8 November)

– Lucia by Lucy Hunter (13 December)

– An ordinary domestic pattern was disclosed by Monica Carroll (17 December)

– Time Zones by Jake Lawrence (30 December)

Editor: Duncan Felton

Designer & Art Director: Finbah Neill

Editorial Assistant: Rachael Nielsen

Readers: Lucy Nelson, Frazer Brown and Kara Griffin-Warwicke

… and we look forward to getting all of this, The Grapple Annual No. 2, to you all soon. Stay tuned and excited.

A shortlist and a call-out

The tiny team at Grapple Publishing was enormously excited last week when it was announced that The Grapple Annual No. 1 is one of three books shortlisted for the Small Press Network’s Most Underrated Book Award 2015!

We’re still enormously excited, but at least the quivering in our digits has stopped enough for us to type out little updates like this. A huge proportion of the praise must go to all of our contributors, the writers and artists who submitted amazing work to make up our first fledgling anthology. A bunch of kudos must also go to the Small Press Network, and all the judges, for putting effort behind a unique award that so brilliantly captures some of the best of independent publishing: highlighting, spotlighting and limelighting previously underrated and underrepresented work.

So now we wait and see what eventuates, with the award night on Friday the 20th of November at The Wheeler Centre in Melbourne. We’ll be there, so see you there? And it’s on the second day of the Small Press Network’s Independent Publishing Conference, so we’ll be there with bells figuratively affixed. For now (and we’re sure the other shortlisted authors and publishers would agree), just to be shortlisted kinda feels like we’re all winners already.

This excitement simply cannot be allowed to stop, so we have another announcement. We’ve just commenced a month-long visual art call-out for The Grapple Annual No. 2! Yup, we were blown away by all the written submissions, we’ve chosen them and we’re well underway editing them for publication. But increasing the proportion of visual art in the Annual is one of our aims, thus: this new call-out.

To submit (and pre-peruse all the details) head to the Submittable page. But the gist is ‘Australian artists, send us a magnificent date-based visual art submission!’ We want it all: comics, photos, illustrations, collage, digital works, anything and everything that’s visual art. We’d love to hear from the emerging and the underrepresented, we’d love to be surprised. And we are, of course, more than happy to discuss stuff and be pitched at also. We’ve got an editor (Duncan), a visual art editor (Fin) and an Assistant Editor (Rachael), ready and waiting.

All going well (though we do things slowly around here), we’ll have a full list of contributors (including our new artists!) announced in late October, with The Grapple Annual No. 2 launched in November, or at least before the year’s out. So much and many excitements!

InstaSaleUpdate!

Hey, been a while. New hairdo? Looks good on you.

Us? We’ve been busy these past few months, busy reading and selecting submissions for The Grapple Annual No. 2. Sorry it has taken us a while! But in fact, we’re just starting to send out responses to all you submitters out there, including a select few acceptance emails. You should be hearing from us within a week or two. Pretty exciting times. We hope to have some public announcements and details (names, titles, dates, etc!) by August. But let us tell you: No. 2’s already shaping us to be a smashing Annual.

Also: Grapple Publishing is now on Instagram. Click us, loveheart us, put filters our hashtags or something. Join us on the journey as we work out what the hell we’re doing signing up for distraction when we should be editing.

And speaking of distraction, there’s no better way to distract yourself from social media than by reading a book. So, for the rest of July, we’re having a little sale: free postage anywhere in Australia for any and all remaining copies of Annual No. 1! So order yours now (maybe even get your favourite date/number if you ask even a little bit nicely).

S-A-L-E !

P-A-R-T-whY?

Because we felt like celebrating, we felt like giving an opportunity to those who haven’t read No. 1 yet, and we felt we had to make room for the impending boxes of Annual No. 2.

We do indeed live in pretty exciting times.

More soon, Grapplers.

2014/2015

As the year nears its end, we here at Grapple have a few final wordgifts for you.

First, we’d like to announce the names of those joining our editorial crew for The Grapple Annual No. 2. These new Grapplers are Rachael Nielsen, Frazer Brown and Kara Griffin-Warwicke. Lucy Nelson and Finbah Neill will fortunately also be sticking around to share their respective (and highly respectable) editorial and design wizardry. It’s great to have them all aboard.

Speaking of The Grapple Annual No. 2: submissions and pitches are still open until February 17. Get onto that.

We’ve also had a few accolades roll in: not only did we receive a stellar review from Katelin Farnsworth at Writers Bloc, we were chuffed to receive this award from Express Media:

What can we say but shucks to the max.

Finally, we’ve put a couple more pieces from Annual No. 1 online, just in time for Christmas. What better time to have a browse and a read? They join a decent sampling of pieces on our website from throughout the Annual’s literary calendar year. More work will be going up now and then throughout the new year. But if you like what you read, do please consider buying a copy of The Grapple Annual No. 1.

Thanks to everyone who has supported us throughout out first year with our first Annual. It’s been a real goodie and you helped make that happen. We hope you have a safe and enjoyable time marking the year’s end, however you go about it. We’ll be looking forward to grappling with 2015 with you.

– Duncan Felton, Editor

This one is true.

– by Eleanor Malbon

(Image credit: martyvis. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 License)

I picked up Dale from the side of the road

just a week before he had picked up a baby pigeon

it clings to his hood as he packs his bags and push-trolley in the back

he tells me that the government covers him for a place to sleep five days a week

but on the other two he has to sort himself out

he’s going to Weston Creek, to Coolo

his hair is cut with blunt scissors

and his beard is sparse

he’s got to be about twenty-three

he can’t work because he’s got no strength in his hands

he tells me they were crushed

he doesn’t say how

eyes roll back into his head as he tells fragments of his story

red hair

blue eyes

freckled hands

weak handshake

silver ring

whole body a dusty blue grey

I don’t even wonder if I could have loved him

or maybe I do, I can’t sort it out in my head

he hunches forward to give the pigeon space between his head and the roof

the heat of the day has well faded now

and I tell him it’s Christmas

he tells me he forgot

politely, he asks what I did today

lunch with the family, wine and cricket in the arvo

when I stop the car he asks

and I give him all the change in my wallet

I don’t have any notes

it’s raining tonight

~

Eleanor Malbon: I write poetry and performance pieces, and conduct research into ecological sustainability. My work often deals with growing up in Canberra, where I still live. I currently work as a tutor and research assistant at the Australian National University.

We Three

– by Sian Campbell

(Image credit: Jonathan McIntosh. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 License)

‘Jee-zus fuh-king Christ,’ G says as we slowly pull into the arrivals pickup area. Gets out, shuts the car door hard. Frankie’s just leaning against the wall, waiting casual as anything, a dirty blue duffel bag at her feet. Her white blouse is sticking to her body with sweat and it’s still only the very early morning, but she looks good – even with the goddamn Santa hat she’s got on. Baby-face, Dad always calls her. The only one of us three whose hair stayed that little-girl blonde. She’s at the wrong airport.

‘You’re at the wrong fucking airport, Frankie,’ I hear G say through the windows, as she snatches the duffel and makes for the boot. Frank gets in the back with Ned and hot air fills the car like a fever breaking out in a body. He makes a move for her straight away, all tongue.

‘Gettoff, it’s too bloody hot.’ Her accent is all wrong and I wonder why I never picked it up on the phone. She pushes his wiry kelpie frame over to the other side of the car and he actually leaves off properly for once. Ned’s getting old – six, or so, now. Has to be. Brittle brown hairs flake the car seat covers all over and I tell myself that Frankie can be the one to give it a vacuum at Dad’s. Avalon. Fuck’s sake.

‘Nice hat,’ I say.

‘Cheers,’ she says.

‘Shut the door already, will you? Why the fuck did you fly to Avalon?’ I ask.

The boot slams and G gets back in the passenger seat, wrenching her feet up onto the old blue esky. I start up the engine again. Twenty or so hours in the car at least until Dad’s. Straight, if we want to get there by Christmas morning. Cloying pangs of dread threaten to suck me under already and we haven’t even got going yet.

‘Why the fuck did you fly to Avalon?’ G asks.

‘Logic dictates that as the passenger, I’m not the one at the wrong airport,’ says Frankie. ‘Maybe you wrote it down wrong.’

‘I don’t even know how you fly to Avalon from London,’ G keeps on.

‘There was a stopover.’

‘You can’t blame us, you know. For thinking you’d be flying to fucking Melbourne airport?’

‘Just cut it out,’ I say. ‘The both of you. Put some music on or something, G.’

G fiddles with the radio, and ‘Winter Wonderland’ comes on. Michael Bublé. Christ.

‘Oh my god, you can’t even believe the snow in London right now,’ Frankie says, looking out the window at the yellow grass. I blast the air-con.

‘If you’re going to be like this the whole fucking trip,’ I say to no one in particular, turning the radio back off, ‘you can damn well walk.’

*

It’s an easy enough drive, once you start, although I’ve never done it before myself. G has made the drive more than a handful of times – stayed with her high school boyfriend long past the relationship’s use-by date and clocked far more hours in the car than any of us felt necessary, after work sent her south and away from his sorry arse. She knows the route, she says, she knows all the good ways. Still, she’s never done it Christmas Eve before, and never without stopping for a night or two on the way.

Frankie and Ned are both asleep in the back seat, huddled awkwardly under Frankie’s giant navy coat. It’s too cold in here – the air-con’s stuffed so there’s no striking any sort of medium between roasting and glacial. When I look at them in the rear-view mirror, I can just make out Frankie’s hand snaking out limply in mid-air. She looks vulnerable suddenly, more vulnerable than ever, and for some reason a weird sort of fear feeling starts trickling up my insides, or maybe it’s just the air-con drying me up. Next to me, G’s scoffing a Sausage & Egg McMuffin from the drive-through and washing it down with a Coke the size of her face. We’ll probably have to stop soon, judging from the way her leg has started to bounce, but Ned will need to go as well and there’s no telling what the cheap coffee I’m sculling will do to my insides, so I don’t pick a fight even though I want to.

‘Frankie still snores,’ G says.

‘Yeah,’ I say.

I remember the day Frankie was born, them handing her to me. How do you like your new sister, Mum said, and I remember thinking that there wasn’t really a good answer. Eight years old, G only a year behind me, and I thought beforehand that it would be nice having a baby around, that maybe it would let me boss it around. That maybe it would be a boy. A brother, because Janet Harrison had a little brother and said he would never have learned how to tie his shoelaces if it hadn’t been for her. Or maybe it’d be another sister but it wouldn’t be one like G, it’d be one that looked just like me, with my dark hair and weird sort of big mouth. Not fierce like G, who never needed me for anything. I thought that maybe in a way I could be its mother and I would have something of my own that G could never take from me.

But then it came out, and it was just Frankie.

*

Our father is old. He has emphysema, and will die soon enough, the doctors say. The fact that he’s having another baby at his age is, quite frankly, the stuff nightmares are made of, but when he calls and says he and Lisa want us all to come there’s no way out of it. You can’t say no to a man who’s dying, G says on the phone. I wire Frankie most of the money from my last gig and tell myself that Ned can probably go without his yearly shots.

*

G pulls over at a rest stop in the middle of nowhere, somewhere in New South Wales I figure, though I stopped paying attention to the GPS hours ago.

‘I need to stretch my legs,’ she says. We both know that what she needs is a smoke. I open the door for Ned and he bounds out, getting almost all the way to the nearby scrub before he realises we’re not following him and heads back.

‘Wake Frankie,’ I tell G. She ignores me. Says, over her shoulder,

‘Going to the loo.’

I head back to the car and pull Frankie’s hair lightly. The soft blonde hair looks out of place in my hard brown hand.

‘Frank. Do you need to pee?’ I notice her hair is a bit matted from rubbing against the back of the car seat and it makes me feel good for some reason.

‘What?’

‘Do you need to pee? We’re at a rest stop.’

She opens her eyes and looks at me.

‘I was having a dream you were being killed,’ she says, ‘and I just had to watch. There was nothing I could do.’

*

‘Come into the dining room,’ Dad said last time. ‘I’ve got something to say.’

The dinner table had been covered with a bunch of Mum and Dad’s belongings, mostly clothes but also jewellery, knick-knacks and some books. Mum’s wedding dress. The weird big painted china jug that used to be in the kitchen.

Dad had been holding a pad of Post-it notes, and as we entered the room he held it up in the air like a ref handing out a yellow card at the soccer.

‘I’m dying,’ he said. ‘You all know that already, and that’s all I want to say about it. And now we’re going to be civil, and you can each pick things out one by one. I didn’t raise any goddamn animals.’ Lisa had already taken a lot of the good stuff anyway. For the baby, she said.

‘Just don’t die on my birthday,’ G told Dad. Mum had died on G’s twenty-third birthday. It came as a bit of a shock to all of us except G. (‘She always made other plans on my birthday anyway,’ said G.)

Later when he was in bed, Lisa had told us about how when Dad’s mother died his five siblings had torn the house apart.

‘Looted the place,’ she said. ‘Your Dad was the only one who lived interstate and by the time he got there the only thing left was a pile of Grandma’s brass dollhouse furniture.’

‘Don’t call her Grandma,’ G had said. ‘She never even fucking met you.’

In the end Frankie had been the one to take the wedding dress. Nobody said a word.

*

On the radio, they’re debating the sexual politics of ‘Baby, It’s Cold Outside’. Progressive, for a commercial station that normally stuck to the latest celebrity crises, or maybe interviews with the Prime Minister if they were feeling particularly political.

‘Does it ever bother you that all the Christmas songs are about snow?’ Frankie asks from the passenger seat. Her Australian licence had expired last year, and she never bothered to renew it. ‘And the way people here put that fake frost stuff on their windows. I don’t know. It just feels wrong, I guess. A bit weird.’

It’s getting dark now and we’ve still probably got at least another eight hours in the car.

‘What are we going to do for dinner?’ I ask.

When we were kids and driving on holiday to Grandma and Grandpa’s, before Grandma died, we’d always pull into a town in the early evening just as everyone started getting hungry, and I never knew if Mum and Dad timed it that way or if it was just one of those things.

‘Look out for those golden arches,’ Dad would say.

‘Why do you think Mum never drove?’ I ask G and Frankie now.

Outside, everything feels quieter somehow even though I know it’s not really. Like the dark has sucked something out of the air. Everything is blue but sort of orange as well and it feels like something I’d forgotten. Like Christmas. Nobody says anything.

‘Yeah,’ I say to Frankie, ‘but have you ever noticed that those songs – ‘White Christmas’ and all that – sort of feel like our Christmases here anyway? Why do you think that is – are we just used to them? Some sort of Stockholm Syndrome, like we’re being brainwashed by the Northern Hemisphere. Globalisation. But that Santa Claus movie, with Tim the Tool Man Taylor. That movie always feels like Christmas Eve to me, for some reason.’

‘I don’t know,’ says Frankie. ‘Not to me.’

‘Whatever happened to Jonathon Taylor Thomas?’ G asks.

Suddenly, the windshield is splattered with little orange lights. We’re coming into town, bang on dinner.

‘Keep a look out for those golden arches,’ says G.

*

‘Hey,’ I say as Brisbane city comes into view. ‘We’re here.’

G and Frankie sit up straight, try and make out where we are.

‘We’re not anywhere,’ G says, but neither of them go back to sleep. Everything looks kind of golden.

‘Oh!’ Frankie says all of a sudden. ‘I guess it’s Christmas Day now.’ We drive the rest of the way in silence.

We pull into the driveway well past four in the morning. Lisa meets us at the door – looks at Ned, pissing on her flowerbed. ‘Your Dad’s sleeping,’ she says. ‘He couldn’t wait up. You know. Merry Christmas.’

I pop the boot and we sling our bags into Frankie’s old bedroom, the only one still the way it was before. Lisa had turned mine into a sewing room the first chance she got. Prime window real estate, she said. We dig out the wrapped parcels and put them under the tree in the corner of the dining room.

‘Don’t get me anything this year,’ Dad had said. ‘Won’t need it where I’m going.’ He meant it. We’d never gotten Lisa anything in the first place.

They’re all for the baby. For her.

‘Can we see her?’ asks Frankie.

‘It’s late,’ says Lisa, but we can tell her heart isn’t in it.

We three crowd into G’s old room. The nursery, now. She’s not even sleeping, just lying there calmly like she was waiting for us. She looks up at our faces – isn’t fazed one bit.

‘Hi,’ says Frankie. There’s nothing much to say or do. It’s just a baby, staring. Nothing else in the world for it to do except drink and sleep and shit. Someone coughs from behind us.

‘Can you believe it?’ Dad says. ‘Another daughter. I’m cursed.’

She is a week old and in a few hours we’ll open her presents for her, the presents we have carried across states and oceans. She won’t understand any of it and the clothes won’t fit for months. Dad will sit in his chair with a cup of coffee.

‘Just imagine,’ he’ll say, and everyone will.

Sian Campbell is a Melbourne-via-Brisbane-based freelance writer and one of the founding editors of Scum Mag. She tweets, blogs, and makes a lot of Christmas mix CDs that no one ever listens to.

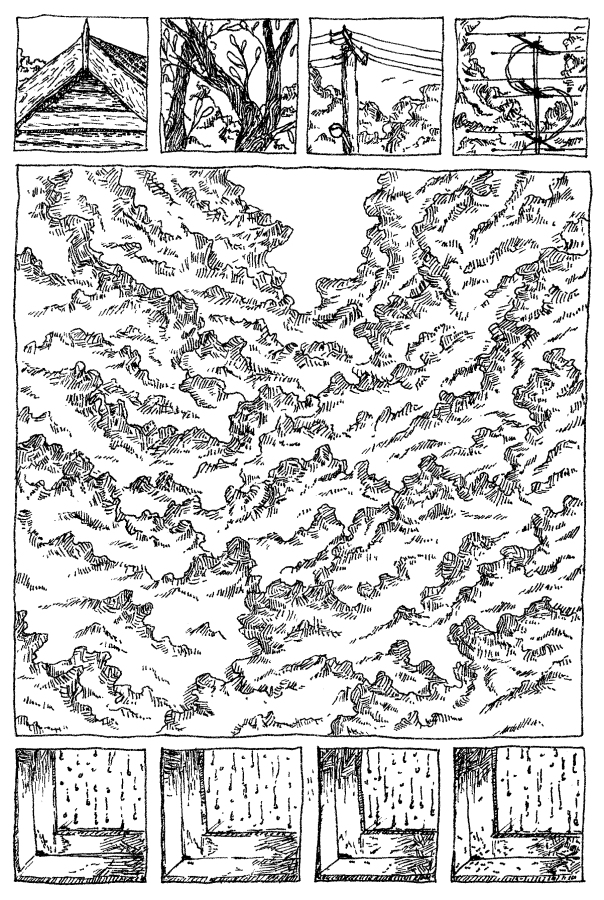

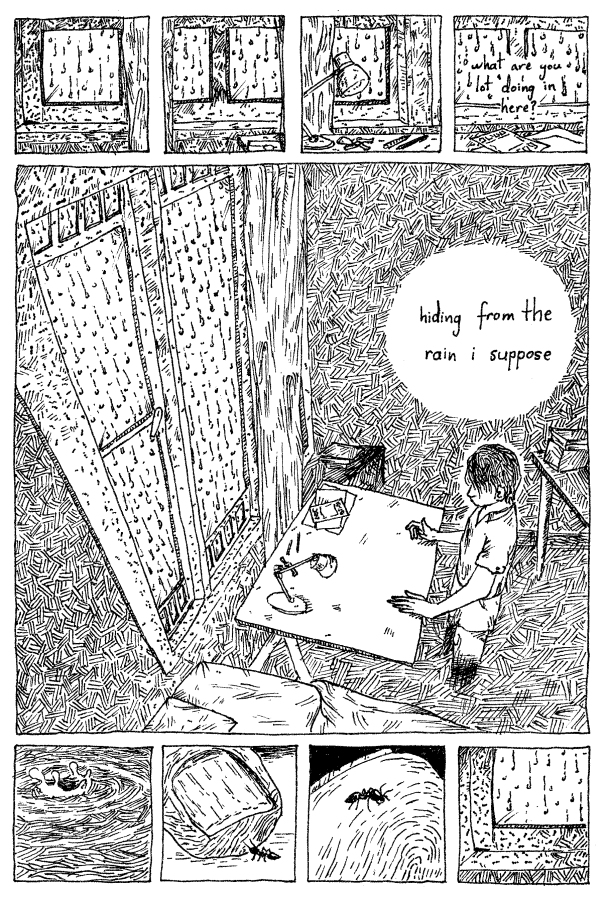

Ants

– by Finbah Neill

Finbah Neill is a Newcastle-based freelance designer, illustrator, and comic maker. He’s the designer at Grapple Publishing, he’s the visual art editor for Voiceworks, he draws weekly illustrations to accompany flash fiction at Seizure Online, and he’s completing a bachelor of Visual Communication Design at the University of Newcastle.

Grim X-pectations

– by Sonya Deanna Terry

(Image credit: MsSaraKelly. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License)

Late last year, I happened across an old theatre programme in a rarely sorted-through cupboard, and immediately designated the booklet to a file labelled ‘Shows’. The file is ragged now and plump with mementos dating back to 1988. The programme my recent clutter clearing unearthed was quite similar to the others: pages crammed with photos of performers, smiling or open-mouthed, gesticulating flamboyantly against backdrops of faux-marble staircases or painted cities. The difference was that the singers prompted a pang of familiarity, not because they were household names – the 1990 production of Funny Girl had been an amateur one held at The Canberra Theatre – but because many of them had become friends. We’d belonged to an exclusive club that focused on footwork, camaraderie, costume alterations, gruelling rehearsals and after-show cocktail events that brought out the show-off in all who showed up.

On the programme’s fourth page was a black-and-white picture of me amongst the other Ziegfeld Showgirls, a shy nineteen-year-old peering out from glittering plumage, wearing the sort of expression that’s typically worn by chorus singers of zero vocal ability, an expression that spells ‘undetected stowaway’. Flicking further through the programme, I recalled the sixties-composed tunes. In every rehearsal and show, I’d gone silent once the orchestra started up, reminding myself that even pop stars lip-synched. True, they at least mimed their own voices, but at that point in time, pretend-singing hadn’t done Milli Vanilli any harm. It would be two more years before that dastardly duo would descend into infamy.

How, you may be wondering, did I ever get into a musical if I couldn’t even sing? The audition panel gave me a dance solo because of my jazz-ballet and belly dance background and suggested I double up as a showgirl/chorus singer. They’d been looking for dancers with reasonable voices whose ‘physical presence conjured the 1920s’. Who would have thought the small mouth I resented would ever become an asset! As for a ‘reasonable voice’, well, let’s just say I have the angels to thank for the tunelessness of my ‘Happy Birthday’ rendition being politely overlooked.

My 1890s-born grandmother had despaired of her own mouth when young. ‘Too broad,’ she’d said, shaking her blue-rinsed head. I’d been amazed. ‘But big smiles are considered attractive,’ I’d told her. She’d looked down wistfully. ‘Now, perhaps. But not back then. In the twenties, we girls were expected to look like kewpie dolls. It improved once World War II came around. Suddenly all the actresses had victory rolls and enormous grins.’

Thanks to Funny Girl I revisited the era of my grandmother’s youth. Atop the magic carpet of costume, script and song, each of us were transported to the innocent optimism of 1914. In ‘Rat-Tat-Tat-Tat’ we marched backwards up a staircase, hoping our golden stilettos wouldn’t stick in the step joins.

Lyricist Bob Merrill’s patriotic lines (‘American boys are all such straight shooters!’ and ‘We’ll take care of him, Mother, when he comes home from the war,’) were designed to echo the propaganda that enticed young men to enlist, and had a discomforting effect on a lot of us. Throughout high school we’d been exposed to horrifying doomsday documentaries that both described nuclear devastation in detail and warned that this was where the Cold War might lead. Some of us had sunk into future-fearing apathy. Some had even suicided. Others had got active in fighting for nuclear disarmament, had roared unashamedly along to the spirited protest songs of that flailing-armed rock star activist whose wildest deeds in more recent years, as our previous Minister for Education, involved shooting goals for Year 3 basketball teams.

Thanks to the threat of World War III and the 1987 AIDS campaigns, pessimism seemed to seep into, and subtly taint, the youthful dreams of Generation X. Few of us could go tenpin bowling without calling up images of the Grim Reaper treating all and sundry like skittles, the theme for a commercial that brought renown to Siimon Reynolds, a 21-year-old advertising exec with a typo for a first-name. The initial hostility of his audiences, many of whom were parents of nightmare sufferers, did not impinge on Reynolds’ rising-star career. He went on to become founder of a marketing and communications company now worth at least $500 million.

The theatre programme threw up one memory after another, the ‘casual shots’ page especially. Here we were sipping Vienna coffees at Gus’, there we were cavorting through autumn leaves.

Ah, Canberra’s ruby-tinted autumn leaves! An event, six years prior to the time of the photo, faintly flitted back. Age fourteen. Trudging alongside a friend through crunchy liquid-amber leaves near the Manuka Cinema. Chattering excitedly about the movie we’d just seen: Back to the Future starring Dolly Magazine pin-up boy, Michael J. Fox, who, throughout those spellbound 116 minutes in his role of time-travelling Marty McFly, transported us into the post-war hopefulness of the 1950s. Fox then had us biting our nails when he returned to 1985 where a scary gang of gun-wielding Libyan nationalists were demanding the return of their nuclear fuel.

The first of two sequels was released in North America on the 20th of November 1989, with an Australian release soon after. Partly set in the year 2015, Back to the Future Part II featured fantastical skateboards that never touched the ground. Since anything might happen in twenty-six years’ time, we teenagers refused to dismiss the idea of hoverboards. We might even be in possession of portable shoe phones by then – like Agent 86 had in the 1960s sitcom ‘Get Smart’ – kept in our pockets though, rather than beneath the sole of one foot, and quite possibly referred to as ‘Smart’ phones. And since we were no longer under the threat of Russia or America pushing that Big Red Button, chances were we would still be alive to enjoy our advanced telecommunication devices, and skating over the clouds. That was if we didn’t all contract HIV first.

AIDS and other grim fears of Generation X were captured aptly in 1994 by the movie Reality Bites starring Winona Ryder, Ethan Hawke and a lesser-known Ben Stiller. Resonating with many Generation X-ers was one of Hawke’s lines. Ryder’s character says: ‘I just don’t understand why things just can’t go back to normal at the end of the half hour like on “The Brady Bunch” or something.’ And Hawke’s character replies: ‘Well, ’cause Mr Brady died of AIDS. Things don’t turn out like that.’ Robert Reed, the actor who had played the lovable flare-wearing dad of a sitcom favoured by many Generation X-ers throughout the seventies, had died two years earlier.

A year later, Christopher Reeve (aka Superman) would sustain a cervical spine injury that would paralyse him from the neck down. Back to the Future’s Michael J. Fox had already been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. On the screen, these actors were invincible. In real life, their humanness and their mortality had become despairingly apparent, and proved to the young and the star-struck that reality did bite at times, and that none of us were ever very far from its jaws.

I closed the theatre programme, pleased my generation’s gloomy expectations were content to remain in the past, and did a quick assessment of the future we’ve all reached. This is the list I came up with:

1 – We’re still alive – and enjoying it.

2 – Michael J. Fox is enjoying being alive, too, having recently starred in ‘The Michael J. Fox Show’, amongst other TV roles.

3 – Our nation is free of the potential perils of the Cold War and to add to this, so far has a thriving economy.

4 – We’re now only a year away from riding on hoverboards. Yee-ha!

5 – The technologies of music, television, movies and the Internet have allowed us choices: we can journey to the past like Marty McFly. Thanks to the sophistication of modern entertainment, we can zoom back to the fifties or the twenties, or to wherever else we choose, and we don’t have to rely on Libyan nuclear fuel to do so.

History is, thankfully, dead, but memory, hope and time-travel are, like us, still very much alive.

Former Canberra resident, Sonya Deanna Terry is a debut novelist, Communications student and rabid theatre-goer. Details of her soon-to-be-released two-volume series Epiphany can be accessed after the 7th of December at: www.EpiphanyTheGolding.com

Callouts

First and at the fore: submissions for The Grapple Annual No. 2 are open from now until February 17th 2015. That’s 3 months to prepare your finest date-based fiction/poetry/non-fiction/comic/art/other submission! Also we’re using Submittable now. So: SUBMIT.

Second and also essential: Grapple Publishing is a publisher on the grow, so we’re expanding our editorial team! Perhaps you’d like to join us? Being only a tiny team, we’re looking for more excellent people to read and select submissions, assist with editing and proofreading and/or to generally assist throughout the whole process of preparing The Grapple Annual No. 2 for launch.

Keen to get involved? Send us a short email (let’s say 500 words max) telling us why you’re interested, why you think it’d be good to have you on the team and what you’d like to get out of it all.

We’re open to people with specific interests (poetry, comics, art, creative non-fiction, etc?) as well as all-rounders. Canberra/ACT-region applicants are preferred, but we’re ready to be convinced that having the right person all the way over your way will be good for Grapple too.

Please note that this is an unpaid opportunity. We’re self-funded and we survive on sales. We pay our contributors and our designer, but none of those on the editorial team gets paid (yet). However, those on the team will be given complimentary copies, snacks and beverages, and as much support, freebies and unwavering gratitude as we can spare.

For all questions and applications send an email to Duncan, our editor: editor at grapplepublishing dot com.

Deadline for these applications is only a fortnight away: November 30th 2014. Once it’s December, no dice.

That’s all for now. We’re super-duper-excited for everyone’s submissions and applications. So get ready, get set, get sending.

He was close

– by D A Shorr

(Image credit: Jamal Fanaian. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License)

Gabe lived next door in a yellow house crowded in on all sides by sycamores. Our mamas collected their buttonballs in wicker baskets each year, insisting we’d craft with them. Once, maybe, we pressed spiky spheres into green paint then rolled them on paper, leaving prints like itch-envy stars – the buttonballs otherwise left to rot. Gabe pushed me to use them in potions when we played witches, running around the house cackling, squawking in high-pitched voices until Papa or my brother told us to play outside.

Years ago, Gabe often explained, our two properties were the same estate. Gabe’s yard had the mansion, carriage house, and gardens; mine was the graveyard. The spirits who lived in my yard, Dusty and Ghost, were bound to haunt the grass around their bodies’ beds. We could only ever coax them a quarter-way across the yard in any direction – kept us mostly to hopscotch and cards – or else had to tow them by hand, straining farther as their tethers pulled taut. Once Gabe found an old map of the property in his crawlspace. The four of us spent the day searching for treasure – turned out to be buried in my brother Marc’s room. We never found the gold, too distracted hoisting Marc’s underwear up the flagpole, climbing to untangle when it caught on sycamore fingers.

When we were eight or nine, Gabe admitted to making the estate up – the map was soaked in tea and burned at the edges – but I have a distinct memory: six years old, alone one evening in the digging-pit, uncovering first green fabric – a sweater – then a shoulder, an arm, old and stiff. I’m not sure how long I sat pouring sand lightly on the shoulder, watching it flow off the side, trying to count the few grains that slid instead through the gaps between the threads. It was a funny feeling to think just beneath was a body – a corpse, Gabe called them in death – and I think this made me cry because I didn’t notice Dusty and Ghost until they put their arms around me and hummed.

. . .

To read the rest of He was close, you can buy a copy of The Grapple Annual No. 1.

Over the 2014 Halloween weekend, we shared D A Shorr’s He was close and Nick Marland’s October 31 in their entirety. Keep an eye out for more free pieces online as their date approaches.

D A Shorr lives in New York City, teaching maths to high school students. He graduated with a degree in mathematics, creative writing, and education, which has prepared him thoroughly for feeling helpless under all the problematic tensions that teaching high school entails.